The Story We Tell Ourselves (And Why It’s Often Wrong)

Last week, a manager vented to me about one of her team members.

“He’s just lazy,” she said. “He missed another deadline.”

A few days later, she learned what she hadn’t seen: His father had been hospitalized. He was juggling doctor visits, childcare, and late nights trying to keep up. The missed deadline wasn’t about laziness. It was about exhaustion and fear.

Nothing about the facts changed — only the story.

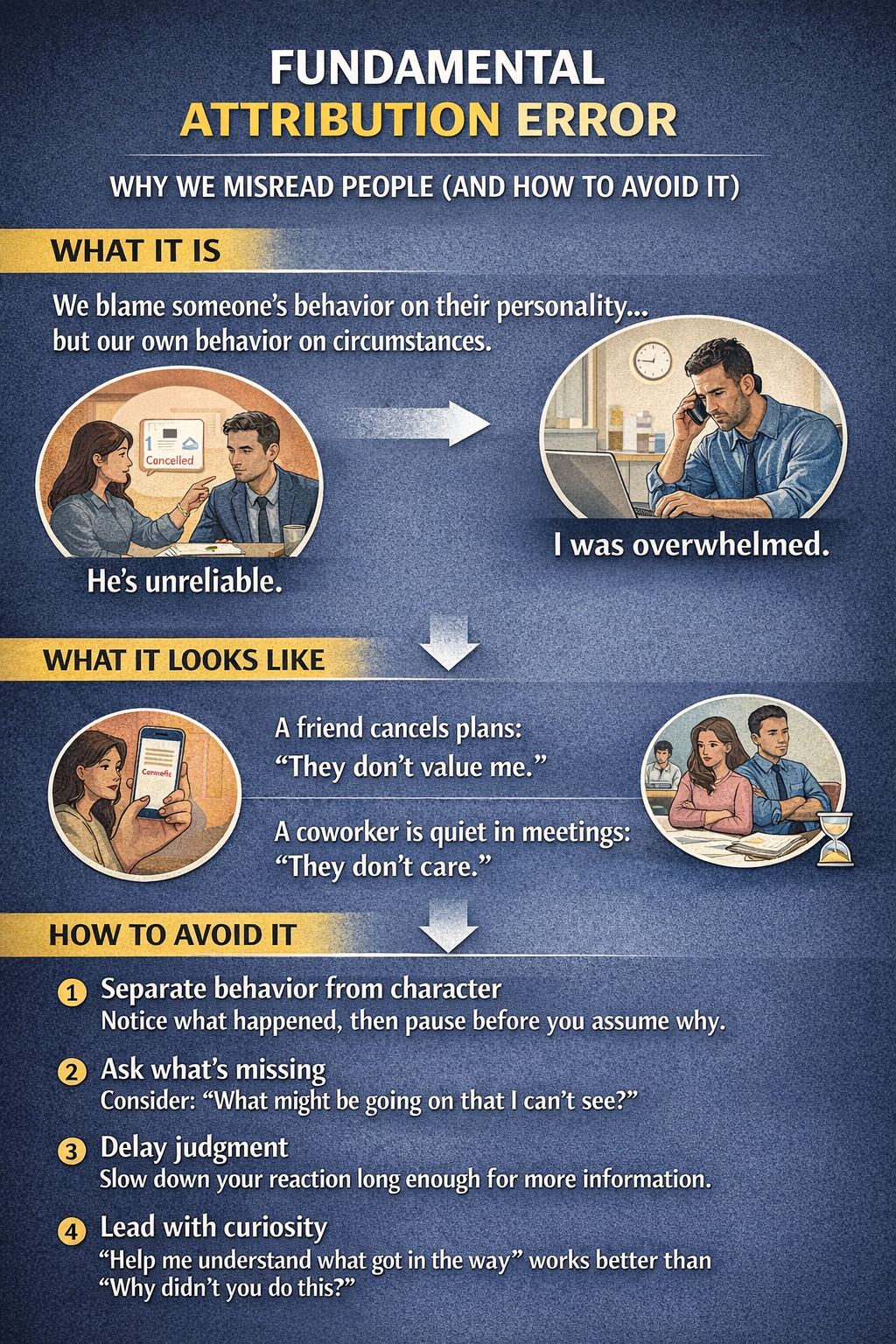

That gap between what we see and what we assume is where fundamental attribution error lives.

What Is Fundamental Attribution Error?

Fundamental attribution error is our tendency to explain other people’s behavior as a result of their personality or character…

…while explaining our own behavior as a result of circumstances.

When they mess up:

“They’re careless.”

“They’re incompetent.”

“They don’t care.”

When we mess up:

“I was under pressure.”

“I didn’t have enough information.”

“It was an unusual day.”

Same behavior. Different explanations.

And we rarely notice we’re doing it.

How It Shows Up in Personal Life

In personal relationships, fundamental attribution error quietly poisons trust.

A friend cancels plans.

“They don’t value me.”

Your partner snaps at you.

“They’re selfish.”

Your teenager doesn’t respond to a text.

“They’re disrespectful.”

We interpret behavior as character instead of context.

But most of the time, what we’re seeing is:

Fatigue.

Stress.

Fear.

Overload.

Distraction.

Unspoken worries.

When we jump straight to judgment, we skip curiosity — and curiosity is where connection lives.

How It Shows Up at Work

In professional settings, the cost is even higher.

An employee misses a deadline → “They’re unreliable.”

A coworker is quiet in meetings → “They don’t care.”

A sales prospect doesn’t respond → “They’re not serious.”

A teacher struggles with classroom management → “They’re just not strong enough.”

We confuse outcomes with intent.

And once we label someone, we stop seeing data.

We stop asking questions.

We stop designing better systems.

Fundamental attribution error turns complex human problems into simple moral ones:

Good vs. bad.

Committed vs. lazy.

Smart vs. incompetent.

That may feel efficient — but it’s almost always inaccurate.

Why Our Brains Do This

Our brains crave certainty.

Attributing behavior to character gives us:

A clear story.

A sense of control.

A moral high ground.

Situational explanations require effort:

Context.

Complexity.

Ambiguity.

And in fast-moving environments — families, schools, businesses — speed often beats accuracy.

So we default to judgment.

Not because we’re cruel…

But because we’re human.

The Real Damage

Fundamental attribution error doesn’t just misread people — it reshapes relationships.

It creates:

Resentment instead of understanding

Discipline instead of support

Distance instead of dialogue

And once a narrative forms, confirmation bias takes over:

Every future mistake “proves” the label.

At that point, you’re no longer responding to behavior —

You’re responding to a story.

How to Be More Mindful (And Avoid the Trap)

You can’t eliminate fundamental attribution error.

But you can weaken its grip.

Here are practical strategies to do exactly that:

1. Separate behavior from character.

Describe what happened without interpreting why.

“He missed the deadline” is data.

“He doesn’t care” is a story.

Train yourself to notice the difference.

2. Ask the missing-context question.

“What might be going on that I can’t see?”

You don’t need to assume the best — just assume you don’t know everything.

3. Reverse the roles.

Ask: “If I did this, what explanation would I give myself?”

That comparison alone exposes the bias.

4. Delay judgment by 24 hours.

Strong emotional reactions are the breeding ground of attribution errors.

Time creates perspective.

Perspective creates accuracy.

5. Lead with curiosity, not correction.

Instead of: “Why didn’t you do this?”

Try: “Help me understand what got in the way.”

Same goal. Different impact.

6. Design better systems before blaming people.

Missed deadlines often mean:

Unclear expectations

Overloaded schedules

Competing priorities

Poor communication

Fixing systems prevents repeated “failures” that were never about character to begin with.

7. Remember: you are also someone else’s ‘them.’

Other people are making attribution errors about you too.

Extend the grace you wish they would.

A Final Thought

Fundamental attribution error isn’t about psychology.

It’s about humility.

It’s about recognizing that behavior is visible — but context is hidden.

And when we treat partial information as the whole truth, we create unnecessary conflict.

The most powerful shift is simple:

From “What kind of person is this?”

To “What might be influencing this moment?”

That single question can change how you lead.

How you love.

How you listen.

And often, how much closer you get to the truth.